Recording runs¶

Design document

This is a design document intended for nextest contributors and curious readers.

When recording is enabled, nextest persists the full event stream, captured test outputs, and workspace metadata for every test run. This information can be used to replay and analyze test runs, and also as the basis for iterative reruns. Getting this right is a challenging problem. Here's how nextest does it.

Design principles¶

- Minimal, clean user interface: Tests being rerun often means the user is having a bad day. Nextest should not make users have an even worse day.

- Encapsulated complexity: Replays and reruns have a great deal of underlying complexity as described below. All of this complexity is encapsulated into its own subsystem. For the most part, neither the user nor other parts of the system, such as the runner loop, need to care about rerun logic.

- Recording failures must not break test runs: A failure in the recording subsystem (disk full, I/O error, corrupted index) should never cause a test run to fail or produce incorrect test results. Recording errors are reported as warnings, and the test run proceeds normally. The recording for that run may be incomplete or missing, but the user's primary workflow is not disrupted. Each run is its own independent fault domain: corruption in one run's data does not affect any other run.

What gets recorded¶

Nextest records three categories of data for each run:

- Test events: A full-fidelity event stream capturing the status and outcome of every test.

- Test outputs: Captured standard output and standard error, stored in a compressed output store.

- Workspace metadata: The output of

cargo metadata, the test list, and a small amount of additional metadata (see Other metadata).

The most essential information is status information for each test and captured output for failing tests. We also choose to record captured output for successful tests. In most cases, this tends to be a pretty small amount of data, and it helps --no-capture work well for replays.

Storage location¶

We store recording information in the system cache directory. We don't use the Cargo target directory because:

- the target directory is an implementation detail of Cargo; and

- recordings should persist across

cargo cleaninvocations.

We use the XDG cache directory (by default ~/.cache) on all Unix platforms (including macOS), and AppData\Local on Windows. On macOS, we could have used ~/Library/Caches, as is common for GUI apps, but nextest is a CLI app, so we use the XDG setting.

Recording format¶

There's a range of reasonable possibilities for the recording format:

- for information about runs: either an event stream or a summary of runs.

- for test outputs: a range of options, from files on disk for every piece of output to SQLite archives.

Global index¶

We store a global index of runs as a Zstandard-compressed JSON file, under projects/<escaped path to workspace>/records/runs/runs.json.zst. This index contains a bounded amount of information per run:

- the run ID.

- the store format version (see Recorded run versioning below).

- the nextest version used for this run.

- the time at which this run started, and when it was last written.

- how long the run took.

- CLI and build scope arguments.

- relevant environment variables.

- the parent run ID for reruns.

- compressed and uncompressed sizes for the run event log and the test output store.

- basic status:

incompleteif the run is in progress or nextest crashed mid-run; test pass and fail counts; and the exit code.

An alternative is to store all test information across all runs in a single file, e.g., a SQLite database. This would allow analysis of a test across runs. But it has downsides:

- Corruption in this file would cause all test information to be lost. Storing separate information per-run makes each run its own independent fault domain.

- We would have to invent a per-run storage format anyway, for portable recordings.

Concurrent nextest invocations can race on writes to the global index. We use flock to serialize access: each writer acquires an exclusive lock before reading, updating, and rewriting runs.json.zst. (This lock is held very briefly while runs.json.zst is being operated on. It is not held for the duration of the test runs themselves.) If the lock cannot be acquired (e.g., because another nextest process holds it), the writer retries with a brief backoff. If a process dies while holding the lock, the OS releases it automatically, so stale locks are not a concern.

If we find it to be valuable in the future, we can always build a SQLite table as derived data. But for reasonable-sized test suites, an in-memory scan is plenty fast (particularly because gathering information by test is an embarrassingly parallel problem). If building an SQLite database proves useful, it would be for other reasons, such as letting users write SQL queries against test run information.

Run event log¶

We choose to serialize information about run events as an event stream as opposed to building a summary collected at the end.

- For events, we use a serialized form of the internal

TestEventtype; this enables full-fidelity replays. (As part of this work,TestEventwas made platform-independent, so that Unix runs can be replayed on Windows and vice versa.)- The serialization of

TestEventis an internal implementation detail that we can change over time (see Recorded run versioning below). It is unlikely to be exposed in this form as a public interface. - We use property-based tests to ensure

TestEventinstances can be round-trip serialized.

- The serialization of

- Another advantage of an event stream over a summary file is that if nextest crashes unexpectedly, existing events are preserved and the run can be reconstructed to some degree.

For storage, we use Zstandard-compressed JSON Lines. Even at the default Zstandard level 3, compression is very efficient: in the nextest repo, a log for 655 passing tests (1316 entries) compresses from 1.4 MiB to 69 KiB (a ~95% reduction).

An alternative is to store entries in a per-run SQLite database.

- Events could be stored as JSON blobs, but we wouldn't benefit from any of SQLite's features in that case. Once the run is finished, the store is read-only, so SQLite's random-access and transactional write capabilities offer no advantage over a simpler append-only format.

- Events could also be stored in a normalized (relational) form, but the test event model is very complex (thousands of lines of Rust) and expressing the complexity in SQL doesn't seem worthwhile. To the extent that data needs to be indexed, it is small enough to store entirely in memory.

Test output store¶

Test outputs (standard output or standard error) are generally quite small: across a representative sample, the p75 of uncompressed standard output is around 208 bytes (see the compression format section for detailed statistics).

Test outputs are also fairly similar. The default libtest standard output is of the form:

running 1 test

test my_test_module::my_test ... ok

test result: ok. 1 passed; 0 failed; 0 ignored; 0 measured; 3 filtered out; finished in 0.00s

By default, tests don't produce anything to standard error. If tests produce output, e.g., from a logging framework, they tend to be similar to each other.

Test output storage¶

We store test outputs as compressed entries in a zip file.

Some alternatives:

- Test outputs could be stored inline in JSON events, but that would bloat the run log significantly. Use cases such as reruns would pay the price for a feature they don't need.

- A tarball would enable efficient compression across standard output and standard error entries, but it wouldn't be possible to randomly access files in it. Random access is required to materialize test outputs during replay.

- With a columnar data store like Apache Parquet, we'd store all standard outputs together and all standard errors together. That would help us achieve better compression without a pre-trained dictionary. But the complexity doesn't quite seem worth it.

- The ideal storage format for small, largely similar text blobs is actually a Git packfile. It provides all the characteristics we need, but creating a packfile is a somewhat expensive process that would have to be done at the end of each test run, or maybe as a periodic equivalent to

git gc. We choose to forgo that complexity and use a zip file.

We store entries by content-addressed hash to deduplicate outputs. This is not generally relevant for individual runs, but it is for stress tests.

Corruption within an output store is handled at three levels. If the zip central directory is damaged, the archive cannot be opened at all, and the replay fails. If required metadata (test list, cargo metadata, dictionaries) cannot be read, the replay also fails, since these are needed to reconstruct events. But if an individual test output entry is corrupted or missing, nextest logs a warning for that entry and continues replaying the remaining events. This means a partially damaged output store still produces a useful replay, as long as the structural metadata is intact.

Test output compression format¶

For compression, we use Zstandard on each individual test output. We also use two pre-trained compression dictionaries, one for standard output and one for standard error. (The two streams tend to have very different output patterns.)

Dictionary-compressed entries in zip files

The zip file format has native support for Zstandard as compression method 93. But that support doesn't include dictionaries. So we compress with Zstandard ourselves and store each entry with no further compression.

Zstandard dictionaries are meant to help with small data compression. Compression algorithms can generally pick up patterns in larger texts, but small pieces of data (like most test outputs) don't contain enough repetition for the algorithm to exploit. To help with this, Zstandard lets users tune the algorithm through dictionaries.

Dictionary training was done in mid-January 2026 by running tests against a representative sample of approximately 30 Rust projects and gathering their outputs. The script to gather repository information lives in the dict-training repo.

The best dictionary sizes were found through empirical testing (they ended up being in the 4-8 KiB range).

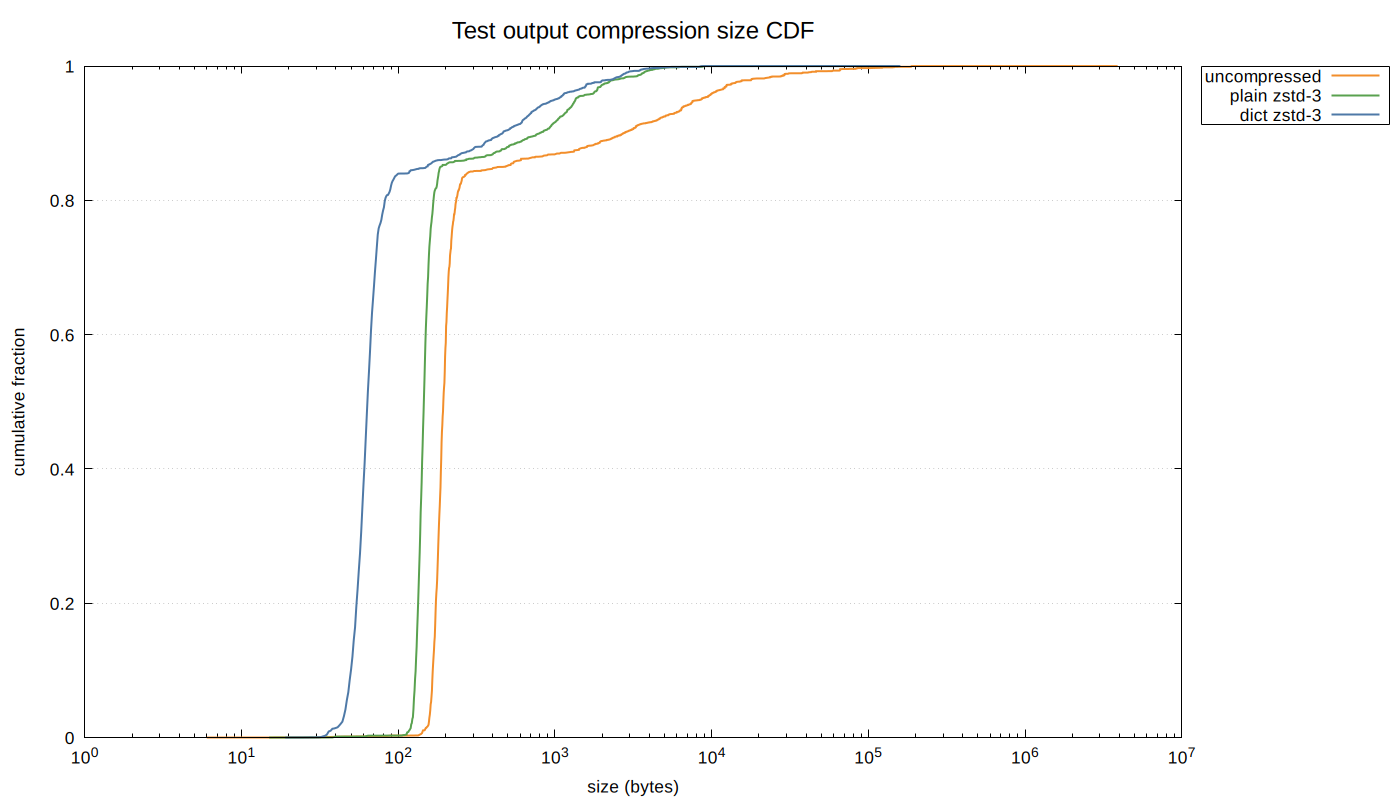

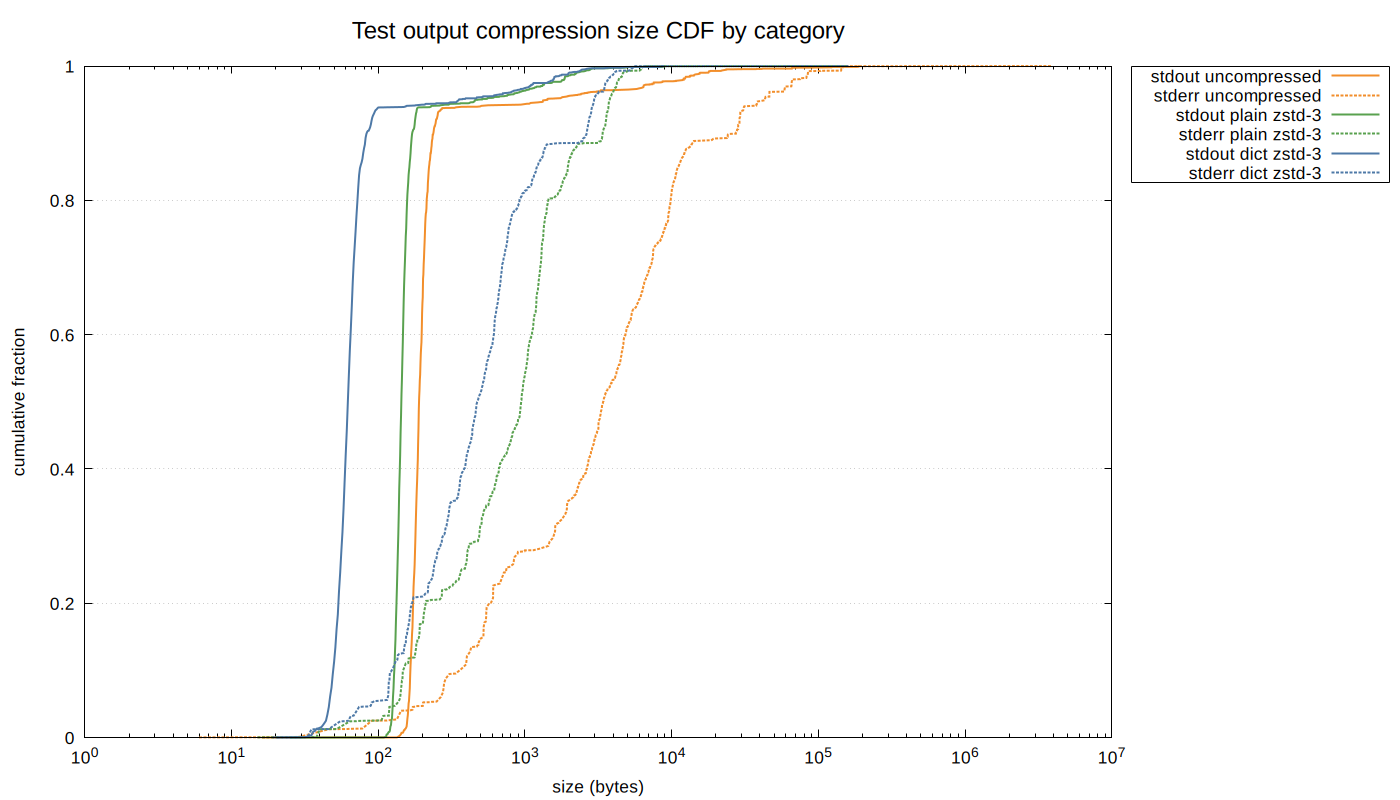

To measure the effect of dictionaries, we analyzed 36,830 test output entries across 200 recorded runs from approximately 30 Rust projects. The following CDF shows the distribution of per-entry sizes for uncompressed data, plain Zstandard (level 3), and dictionary-compressed Zstandard:

The dictionary shifts the compressed size distribution significantly to the left: at the median, dictionary compression produces 64-byte entries versus 146 bytes for plain Zstandard (a 56% reduction). The effect is especially pronounced for standard output entries, which are smaller and more uniform. Standard error entries are larger and more varied, but the dictionary still provides substantial improvement:

The following tables summarize the per-entry size distribution (in bytes) across all entries combined, and broken out by standard output and standard error.

All entries (36,830 entries):

| p50 | p75 | p95 | p99 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncompressed | 194 | 220 | 8,533 | 38,071 |

| Plain zstd-3 | 146 | 161 | 1,354 | 3,687 |

| Dict zstd-3 | 64 | 75 | 997 | 2,850 |

Standard output (32,726 entries):

| p50 | p75 | p95 | p99 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncompressed | 190 | 208 | 1,424 | 15,622 |

| Plain zstd-3 | 144 | 155 | 481 | 2,256 |

| Dict zstd-3 | 63 | 70 | 355 | 2,000 |

Standard error (4,104 entries):

| p50 | p75 | p95 | p99 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncompressed | 3,412 | 8,691 | 43,188 | 84,893 |

| Plain zstd-3 | 943 | 1,336 | 3,780 | 4,661 |

| Dict zstd-3 | 474 | 768 | 2,961 | 4,084 |

The data and charts can be regenerated from local nextest cache data using internal-tools/zstd-dict:

cd internal-tools/zstd-dict

cargo run --release -- dump-cdf > compression_data.txt

make

The currently shipped dictionaries are stored in the nextest repo. At recording time, dictionaries are embedded in each zip file, so we can update the dictionary in the future without needing to do a version bump.

Other metadata¶

For each run, we also collect and store in the zip file:

- the output of

cargo metadata. - the test list in a machine-readable format.

- a small amount of additional metadata.

This information is used to reconstruct replays and reruns.

These outputs tend to be large. In the nextest repo, as of commit a49023f3:

- uncompressed

cargo metadatais 2,326,042 bytes - uncompressed

cargo nextest list --message-format jsonis 98,800 bytes

Files this large don't benefit from dictionary compression, so we store them as regular Zstandard-compressed entries (compression method 93).

The metadata is often the same across nextest invocations, so there are some gains to be had from using a content-addressed store to deduplicate these outputs across runs. But then one would have to worry about refcounts and garbage collection. This is a potential future optimization.

Recorded run versioning¶

With full-fidelity events, we would like to avoid painting ourselves into a corner where we can't change those events. To avoid this outcome, we use two different versions:

- The format version for the global

runs.json.zstindex. - A store format version for each run.

runs.json.zst is designed to have an additive schema. If an older version of nextest encounters a runs.json.zst with a newer format version, it will be able to read from it, but it will refuse to write to the index since writes might cause data loss in unknown fields.

The store format version is not additive. We use two version components, major and minor. If a version of nextest encounters a store format version with a major version different from the one it recognizes, it will refuse to read the file.

- A newer version of nextest encountering an older store format major version will print out the nextest versions that support that store format version. (Not yet implemented.)

- If an older version of nextest encounters a newer store format major or minor version, it will tell users to update their copy of nextest.

Bumps to the store format version are currently done manually. We have plans to automate this using JSON schema support.

Record retention and pruning¶

With any kind of caching comes the need for eviction. Nextest defines a set of cache limits for recorded runs, and prunes runs when those limits are hit.

The default nextest limits are specified in the user-facing documentation. These limits are chosen to be relatively generous and should cover most reasonable use cases. Users who need different values can adjust their limits in user configuration.

Nextest automatically prunes the cache once a day, or if the number or size limits are exceeded by a factor of 1.5 or more. This 1.5x buffer exists to avoid pruning on every nextest invocation (particularly when the limit on the number of runs is exceeded).

Reruns¶

The rich storage format described in the section above enables reruns of failing tests. With cargo nextest run --rerun <run-id>, nextest looks at <run-id> (called the parent run) and determines which tests need to be rerun. This is non-trivial because test lists can change between runs, and nextest needs to track which tests are outstanding (need to pass) versus passing (already passed in this rerun chain).

An interesting consequence of full-fidelity recordings is that reruns can be done not just from the latest test run, but also from any prior state. The design of the recording system naturally supports a tree of reruns rather than a linear chain. We expose this structure to the user via cargo nextest store list.

Rerun algorithm¶

The rerun system maintains two sets of tests:

- Passing: Tests that were last seen to have passed in the rerun chain.

- Outstanding: Tests that still need to pass.

The rerun algorithm is straightforward:

- Using the decision table below, setting R to the parent run, compute the passing set. (All complexity is encapsulated in the rerun decision table.)

- Run all tests that are not in the passing set.

The outstanding set is not used to determine which tests to execute, but it is carried forward to child runs so they can compute their own passing set.

Rerun decision table¶

For a run R, the decision for each test depends on three factors:

- Test list and filter: Is the binary/test present in R's test list, and did it match any filters provided?

- Outcome: What happened when the test ran in R?

- R's parent status: Was this test passing or outstanding in the parent of R? A test that isn't in either the passing set or the outstanding set is unknown.

(If the run R was an initial run, it does not have a parent, and the parent status is unknown for all tests.)

Decision table logic is invoked for the parent run

In normal use, the decision table logic is invoked where R is itself the parent run passed in via -R/--rerun. So in the table, R's parent is the grandparent of the current run. The decision table logic does not use the test list computed for this run.

Put another way, the passing and outstanding sets for a run could in principle be computed and stored at the end of the run. We do this computation at the start of the child run, however, since we want to be resilient to nextest crashing and not getting the chance to compute these sets at the end of the run.

| # | test list and filter | run R outcome | status in R's parent | decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | binary not present | * | passing | passing |

| 2 | binary not present | * | outstanding | outstanding |

| 3 | binary not present | * | unknown | not tracked² |

| 4 | binary skipped | * | passing | passing |

| 5 | binary skipped | * | outstanding | outstanding |

| 6 | binary skipped | * | unknown | not tracked |

| 7 | test not in list | * | passing | not tracked |

| 8 | test not in list | * | outstanding | outstanding |

| 9 | test not in list | * | unknown | not tracked |

| 10 | test in list, matches | passed | * | passing |

| 11 | test in list, matches | failed | * | outstanding |

| 12 | test in list, matches | not seen¹ | * | outstanding |

| 13 | test in list, matches | skipped (rerun) | * | passing |

| 14 | test in list, matches | skipped (explicit) | passing | passing |

| 15 | test in list, matches | skipped (explicit) | outstanding | outstanding |

| 16 | test in list, matches | skipped (explicit) | unknown | not tracked |

| 17 | mismatch (rerun, already passed) | * | * | passing |

| 18 | mismatch (explicit) | * | passing | passing |

| 19 | mismatch (explicit) | * | outstanding | outstanding |

| 20 | mismatch (explicit) | * | unknown | not tracked |

¹ "not seen" means the test was scheduled but no finish event was recorded for it. This can happen if the run is cancelled or if nextest crashed mid-run.

² If a test is "not tracked", it is not stored in either the passing or the outstanding sets. For subsequent runs, it becomes unknown, similar to if a brand new test is added.

Rerun decision table considerations¶

Given a run R, which tests should the child run execute? As the above table indicates, this is a surprisingly challenging problem.

The easy case is that the set of tests to run hasn't changed (rows 10-12 in the decision table). In that case, we run tests not known to be passing (rows 11-12).

There are a number of harder cases, though. They can generally be categorized into operations that grow the set of tests to run, and operations that shrink the set. (Though a single rerun can do both of these things, the analysis can be decomposed into these two categories.)

Operations that grow the set¶

Users can grow the set of tests to run in several different ways:

- Add a new test to an existing binary. In R, the user adds a new test to an existing test binary. In R's parent, the status for these tests is unknown.

- Expand the set of tests through filters. For example,

cargo nextest run -- my_testfollowed bycargo nextest run -R latest. The first command only runs tests that havemy_testin the name. The second command runs all discovered tests. In R's parent, the status for these tests is unknown. - Build another test binary. For example,

cargo nextest run -p my-packagefollowed bycargo nextest run -R latest --workspace. In this case, the second command attempts to run all discovered tests throughout the workspace.

In all of these cases, the status in R's parent is unknown, and in R it falls under "test in list, matches". Therefore, all of these cases are covered by rows 10-12. (The asterisk under "status in R's parent" includes the unknown state.)

Operations that shrink the set¶

Users can also shrink the set of tests to be run in ways mirroring operations to grow the set:

- Remove a test from an existing binary. This is an atypical situation in which a test is deleted from an existing binary. (Another way this can arise is if an alternative set of feature flags is provided.) This is covered by rows 7-9 above: if a test was outstanding or unknown, it stays that way. But if a test was previously passing, it is no longer tracked (and so becomes unknown). If we ever see this test again, we'll rerun it, even though the last time it was seen it passed.

- Skip a test through filters. For example,

cargo nextest runfollowed bycargo nextest run -R latest -- my_test. This is a common workflow for iterative convergence: you see a bunch of tests fail, then you rerun them one by one. For skipped tests, this is covered by rows 18-20: the status is carried forward. - Don't build or list a test binary. For example,

cargo nextest runfollowed bycargo nextest run -R latest -p my-package(will not build other test binaries), orcargo nextest run -R latest -E 'package(my-package)'(will build but not list other test binaries). This is covered by rows 1-6: the status is carried forward.

There is an asymmetry between operation 1 (removing a test from an existing binary) and the latter two (skip a test through filters, don't build or list a test binary) for passing tests:

- With the first case, the test is no longer tracked.

- With the other two cases, the passing status is carried forward.

This difference is because the first case is expected to be much rarer than the other two. In that kind of strange situation, we bias towards being conservative. But this conservatism is not feasible for the more common cases of rerunning subsets of tests, and we carry forward the passing status in those cases.

Other rerun cases¶

Row 17 is the case where the test passed somewhere in R's ancestor chain. In this case, we treat it as passing.

Rows 13-16 should not occur in normal operation, since skipped tests are exactly the set that doesn't match the filter. But they are representable in the event stream. We could either reject these cases as malformed input or handle them similarly to rows 17-20. We choose the latter, primarily because it is more convenient.

Rerun decision table validation¶

The decision table is quite complex. It is rigorously validated through the following techniques.

Property-based testing with proptest. Three properties are tested against the real implementation and randomly generated rerun chains:

-

System under test matches oracle: The implementation (

compute_outstanding_pure), written in an iterative form, is compared against an oracle (compute_rerun_info_decision_table) that uses the decision table directly. The implementation and oracle are written in structurally different styles so that bugs in one are caught by the other. -

Passing and outstanding are disjoint: A test cannot be in both sets simultaneously.

-

Matching tests with definitive outcomes are tracked: Tests that match the filter and have a definitive outcome (passed, failed, not seen, or skipped due to rerun) end up in either the passing or outstanding set.

The proptest generators create a rerun model representing an initial run plus a number of reruns. During reruns, tests can appear, disappear, change filter status, and have varying outcomes across runs. The model is constructed carefully to ensure that the random inputs exercise all rows of the decision table.

Formal verification of the decision table. Since the domain of the decision table is finite, key properties are formally verified through exhaustive enumeration:

-

Passing monotonicity (rows 10, 13, 14, 17, 18): A passing test stays passing under non-regressing conditions.

-

Convergence (rows 10, 13): Outstanding tests become passing when they pass. The only way out of outstanding is to pass.

-

Failure handling (rows 11, 12): Failed or not-seen tests become outstanding regardless of previous status.

-

Test removal behavior (rows 7–9): When a test disappears from the list, outstanding status is preserved but passing status is dropped. This ensures tests that disappear and reappear are rerun.

The formal verification of the decision table, combined with property-based testing that verifies the implementation matches it, provides a high degree of confidence in the correctness of the rerun logic.

Build scope arguments¶

If someone runs cargo nextest run -p my-package followed by cargo nextest run -R latest, which packages should the second command build?

A naive approach would result in the entire workspace being built1, and the set of tests effectively growing. But that is generally not what one expects when trying to converge towards a passing test run.

Based on this, what nextest does is capture the build scope arguments during the initial run, and use that build scope by default for all subsequent reruns. So cargo nextest run -R latest would build exactly my-package.

Which arguments count as build scope?¶

We need to determine which arguments passed to nextest count as build scope arguments.

Clearly, this must be a subset of arguments passed through to Cargo, since nextest delegates to Cargo for the build. So test filter arguments like -E are not build scope arguments.

Looking at the arguments passed into Cargo:

Package selection:

-p, --package <PACKAGES> Package to test

--workspace Test all packages in the workspace

--exclude <EXCLUDE> Exclude packages from the test

--all Alias for --workspace (deprecated)

Package selection arguments are the main driver for having build scope logic, so these arguments must count as build scope arguments.

Target selection:

--lib Test only this package's library unit tests

--bin <BIN> Test only the specified binary

--bins Test all binaries

--example <EXAMPLE> Test only the specified example

--examples Test all examples

--test <TEST> Test only the specified test target

--tests Test all targets

--bench <BENCH> Test only the specified bench target

--benches Test all benches

--all-targets Test all targets

Target selection arguments, if not controlled, can grow or shrink the set of tests to run in a way that users might not expect. These arguments are build scope arguments.

Feature selection:

-F, --features <FEATURES> Space or comma separated list of features to activate

--all-features Activate all available features

--no-default-features Do not activate the default feature

Feature selection arguments are a harder call, but we count these as build scope arguments as well because they too can grow or shrink the set of tests to run.

Compilation options:

--build-jobs <N> Number of build jobs to run

-r, --release Build artifacts in release mode, with optimizations

--cargo-profile <NAME> Build artifacts with the specified Cargo profile

--target <TRIPLE> Build for the target triple

--target-dir <DIR> Directory for all generated artifacts

--unit-graph Output build graph in JSON (unstable)

--timings[=<FMTS>] Timing output formats (unstable) (comma separated): html, json

Manifest options:

--manifest-path <PATH> Path to Cargo.toml

--frozen Require Cargo.lock and cache are up to date

--locked Require Cargo.lock is up to date

--offline Run without accessing the network

Other Cargo options:

--cargo-message-format <FMT> Cargo message format [possible values: human, short, json,

json-diagnostic-short, json-diagnostic-rendered-ansi,

json-render-diagnostics]

--cargo-quiet... Do not print cargo log messages (specify twice for no Cargo

output at all)

--cargo-verbose... Use cargo verbose output (specify twice for very

verbose/build.rs output)

--ignore-rust-version Ignore rust-version specification in packages

--future-incompat-report Outputs a future incompatibility report at the end of the build

--config <KEY=VALUE> Override a Cargo configuration value

-Z <FLAG> Unstable (nightly-only) flags to Cargo, see 'cargo -Z help' for

details

These options generally do not affect the test set, so nextest does not consider them build scope arguments. (--target is an exception in that cross-compilation can affect the test set. But we do not consider it to be a build scope argument. If users are cross-compiling, they're already used to passing in --target for every command, so it's reasonable to expect them to do the same for reruns.)

In summary, the set of options that determine the build scope are exactly the arguments under Package selection, Target selection, and Feature selection. This categorization can be communicated to users directly.

Overriding build scope arguments¶

What happens if a user specifies their own build scope arguments as part of a rerun? There are several options here:

- Override the stored build scope arguments from the original run, but do not use them for subsequent reruns.

- Override the stored build scope arguments from the original run, and use them as the new default build scope for subsequent reruns.

- Use the union of the stored build scope arguments and the ones passed in, i.e., always grow the test set.

- Use the intersection of the stored build scope arguments and the ones passed in, i.e., always shrink the set.

- Override the stored build scope arguments from the original run, and use the union of the stored build scope arguments and the ones passed in as the test set.

- Some kind of more complex set of heuristics depending on the test filters being passed in, etc.

For our implementation, we choose option 1. It is appealing because it is simple to implement and straightforward to explain, and it does the right thing most of the time.

Option 2 seems worse than 1 because it means that a test set shrink operation becomes sticky. This is generally unexpected.

We rule out options 3 and 4 because there are legitimate reasons to both grow and shrink the set.

Option 5 is quite interesting. The idea of this option is that for an individual rerun, we allow both growing and shrinking the set, but that these arguments result in a "high water mark" for future reruns.

Unfortunately, calculating the union is quite complex, particularly in the presence of --exclude and features. Instead, if we don't see a previously-failing test in the set, we report it at the end of a rerun as "N outstanding tests not seen". We may refine this presentation in the future.

Option 6 would be difficult to explain and for users to build a mental model around.

Portable recordings¶

One of the advantages of the richer model of treating test runs as addressable objects is that test recordings can be portable. For example, a recording could be performed on a CI system and then downloaded locally to be replayed.

To do this we define a portable recording format. A portable recording is a zip file that's a combination of the run event log, the output store, and the information about a run stored in runs.json. The -R option accepts a path to a portable recording as an alternative to a run ID or latest (recordings are required to end with .zip, so there's no ambiguity).

Portable recordings have their own versioning scheme with major and minor versions, following the rules described in Recorded run versioning above.

Portable recordings contain the full captured output of every test in the run. Test outputs can inadvertently contain sensitive data: API keys in error messages, PII in test fixtures, or environment variable values. Scrubbing and redacting portable recordings is a very difficult problem, so nextest does not attempt to solve it. Users are responsible for ensuring that recordings shared outside their organization do not contain sensitive information.

The output store is stored without further compression. Storing the output store with compression would save 15-20% in space (owing to zip headers and per-entry metadata being compressed), but would require extracting the archive: random access into a compressed stream requires something like the Zstandard Seekable Format. We expect compressed transfers with Content-Encoding to recover these gains in transit.

Related work¶

Nextest's record and replay feature uses many techniques from various prior systems, combining them in a way that appears to be novel.

Full-fidelity replays are inspired by similar systems in other domains: rr and other record-replay debuggers, and video game replay systems (e.g., StarCraft, Dota, and fighting games). These systems work at different levels (rr works at the syscall level), but all capture structured events to replay them later.

Terminal session recorders like script record raw bytes written to the terminal. Unfortunately, this model cannot be extended to scenarios like cargo nextest replay --no-capture.

Event stream serialization is an example of event sourcing, where events act as the source of truth. This is a well-documented pattern in the distributed systems literature, related to write-ahead logs in databases. (Event sourcing is quite verbose, but has numerous benefits even outside of full-fidelity replays. Nextest's reporting was written in this style from the beginning.)

Content-addressed storage is a popular strategy for deduplication. It was popularized in developer tooling by version control systems like Git and Mercurial.

Dictionary compression is ideal for the use case of many similar pieces of small data, as documented on the Zstandard website. We were unable to find any open source prior art applying dictionary compression to test outputs, but it is likely some prior art exists.

For reruns, some other test runners do failed run tracking: pytest has --last-failed and RSpec has --only-failures. But nextest appears to be the first runner to not just store the last run but also allow rewinding to earlier states. This ability is a downstream consequence of nextest's more sophisticated data model where all test events are logged on a per-run basis. Nextest also has robust, formally verified support for growing and shrinking the set of tests to run, with special attention paid to typical and atypical developer workflows.

Hermetic build systems like Bazel and Buck2 also solve the "what needs to rerun" problem, but they operate on builds by assuming that build outputs are pure functions of inputs. A notable characteristic of tests is that test results are often not pure functions of inputs, so convergence needs to be approached differently. Generally speaking, simpler example-based tests are more likely to be pure functions than complex integration or property-based/randomized tests.

Cloud-hosted test analytics platforms (Datadog CI Visibility, Buildkite Test Analytics, and others) also store test results across runs and provide cross-run analysis such as flake detection and performance trends. These operate at a different point in the design space: they are centralized services that ingest test results after the fact, rather than local-first systems that participate in the test execution loop. Nextest's recording system is designed to work offline and to feed directly into reruns, but the data it produces could also be exported to such platforms.

Some tools and CI platforms do test impact analysis: they determine what tests to run based on code differences since some known-stable version. Reruns solve an adjacent problem: after establishing the set of tests to run upfront, reruns iteratively converge towards all tests passing. Nextest doesn't currently do test impact analysis, but it could in the future.

Test summaries like JUnit (which nextest can output) can potentially be used for rerun analysis. But they are not full-fidelity, not resilient to arbitrary interruptions, and there is nowhere to store the passing and outstanding sets from the run's parent.

Using property-based tests to ensure lossless roundtrips is a standard technique in the literature. Oracle-based testing and exhaustive verification of a decision table are well-known techniques from high-assurance domains.

Many of the UX details such as unique prefix highlighting are directly inspired by Jujutsu. We are deeply indebted to Jujutsu for showing what excellence in dev tools looks like.

Last substantive revision: 2026-02-03

-

Specifically, the set of default members in the workspace. If this field is not specified, then the entire workspace is built. ↩